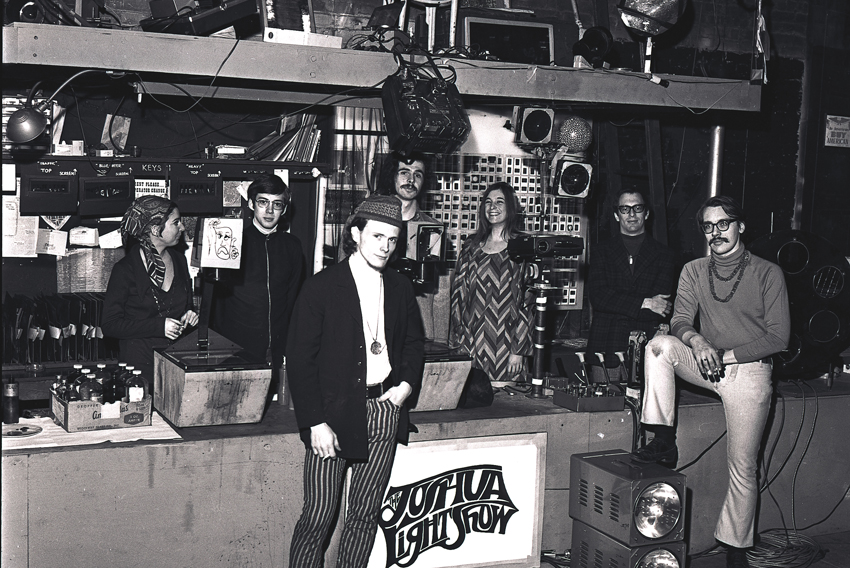

JOSHUA LIGHT SHOW 1967-68

(L-R) STEPHANIE MAGRINO, JOSHUA WHITE,

WILLIAM SCHWARZBACH, JIMMS NELSON,

JANE NELSON, HERB DREIWITZ, THOMAS SHOESMITH

Writing for the New York Times in a 1969 article titled “You Don’t Have to Be High,” Barbara Bell reported on her sojourn to Bill Graham’s Fillmore East rock club on “freaky Second Avenue,” where she saw the Joshua Light Show produce “Mondrianesque checkerboards, strawberry fields, orchards of lime, antique jewels, galaxies of light over a pure black void and, often, abstract, erotic, totally absorbing shapes and colors for the joy of it—each a vision of an instant, wrapped in and around great waves of sound . . . first-nighters stagger out dazzled, muttering to themselves about amoebas in colored water.”

Such associative attempts at articulating the character of psychedelic light shows were not uncommon. Visual music historian William Moritz wrote that, in its finest instantiations, light shows constituted “a living art work of organic complexity considerably more interesting, challenging and satisfying than any of the flat, static art styles of the past, including painting and the traditional fictional cinema.” Curator Christoph Grunenberg has written that of the scores of light shows that arose in the mid-to-late 1960s, the Joshua Light Show was “the most complex and sophisticated.”

The original members of the Joshua Light Show were resident artists at the Fillmore. From March 8, 1968, until the venue closed in on June 27,1971, the group performed multiple shows every weekend for up to a total of ten thousand people, receiving nearly equal billing to such acts as the Who, the Doors, the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Albert King, Chuck Berry, and Iron Butterfly. Joshua White, who had studied electrical engineering, theatrical lighting, and magic-lantern techniques at Carnegie Tech and filmmaking at the University of Southern California, where he made a number of stop-motion and direct animation shorts, founded the group. The JLS consisted of six to eight members during its initial run, with the most stable lineup including White, Tom Shoesmith, and Bill Schwarzbach, who met at Columbia University while studying theatrical lighting and electrical engineering; Cecily Hoyt, a photographer and painter; and Jane Ableman, an art student.

The group employed a panoply of image-making apparatus to achieve diverse visual effects: three film projectors, two banks of four-carousel slide projectors, three overhead projectors, hundreds of color wheels, motorized reflectors made of such materials as aluminum foil, Mylar, and broken mirrors, two hair dryers, watercolors, oil colors, alcohol and glycerin, two crystal ashtrays, and dozens of clear glass clock crystals. White and his cohort designed a rear-projection system, situated roughly twenty feet behind the Fillmore stage, where several tons of equipment was arrayed on two elevated platforms.

The conventional seated theater setup of the Fillmore, however, meant the group focused their efforts on a single screen rather than attempt to establish a West Coast or discotheque-style overall light environment. Using eight 1,200-watt airplane landing-strip lights to project imagery onto a twenty-by-thirty-foot vinyl screen, JLS built their shows from four elements. The first involved the projection of pure colored light through various handmade and modified devices. The second element was concrete imagery, which included film footage shot by the group, hand-etched film loops, segments from commercial cinema, and, eventually, closed-circuit video, which was used to project enlarged images of the musicians performing onstage in real time. The group’s collection of concrete imagery also included hand-painted slides, slides containing geometric patterns, historical art slides featuring paintings by Goya and Manet, and slides consisting of text such as the line attributed to both Warhol and McCluhan, “Art is anything you can get away with,” or the self-reflexive and audience-ingratiating “The Joshua Light Show: A Product of Stoned Age Technology.”

The third element is what the group calls the “wet show”: colored oil and water dyes that were combined in the glass clock faces and displayed via overhead projectors without any photographic mediation. Hoyt and Schwarzbach, who were lovers at the time, were the resident experts in this technique and were able to achieve a variety of effects from the group’s voluminous collection of hundreds of dyes. They could produce wispy, smokelike trails of intertwining color or shape-shifting blobs (likely the “amoebas in colored water” referenced by Bell) that were created by pressing a smaller clock face against a larger one, sending the oil-and-water mixture to the edges of the container in a manner that could be precisely matched to the rhythms being played on the Fillmore’s stage. Shoesmith has described Hoyt and Schwarzbach’s combined efforts as “extremely sensual and erotic, with a lot of building and pausing, like an abstraction of Beethoven’s symphonies.”

The fourth element was dubbed “lumia” and was a technique unique to the Joshua Light Show. The name comes from Thomas Wilfred’s color organ experiments, which began in the 1920s. Indeed, Wilfred’s work proved a profound influence on White, who recalls spending hours every week after high school looking at the artist’s boxes of swirling light at the Museum of Modern Art. In terms of the JLS performances, lumia was Shoesmith’s domain. While inspired by Wilfred, Shoesmith used very different methods of his own creation to shape the light. He occupied the top platform behind the Fillmore screen by himself, where he manipulated reflected and refracted light via a series of mirrors, reflective Mylar sheets, hand-built motorized broken mirror wheels, and projectors.

The Joshua Light Show’s craft-based ephemeral cinema results in a staging that details and commingles nearly the entire history of the projected image. Its use of projected and reflected light is a practice that dates to religious ritual in ancient Egypt and Greece. The group’s magic-lantern techniques date back to the mid-seventeenth century. The display of artisanal film loops alongside examples culled from the entire history of industrial cinema illustrates the heterogeneity of moving-image conventions. New computer-based effects and digital projection systems demonstrate the continuous mutability of shaping light in time. Combined together, the Joshua Light Show epitomizes what Kerry Brougher has cited as the maximalist trajectory in sixties filmmaking, wherein artists saturated “the information in the frame, pushing the image to such a complex and multi-level state that film was shoved up against its boundary lines of possibility.”

And that is what the Joshua Light Show was and continues to be—a reservoir of the moving image’s memory, unmoored in an ephemeral celebration of its possibilities.

—Greg Zinman, © 2012 www.handmadecinema.com